“IQ by profession” refers to the observed differences in average IQ scores across occupational groups. The phrase is often misunderstood as a rigid rule that dictates which jobs people can or cannot do. In reality, it describes a statistical pattern at the group level, not a requirement or a limit for individuals.

Research in psychology and labor economics has long examined how general cognitive ability often measured by IQ tests relates to job performance, training speed, and occupational complexity. This article explains what IQ by profession actually means, why average IQ levels differ across jobs, and how these findings should be interpreted responsibly.

IQ , or Intelligence Quotient, is a standardized measure of general mental ability (often referred to as g), which includes reasoning, problem-solving, learning speed, and information processing. In occupational research, IQ is not viewed as a measure of worth or talent, but as a predictor of how efficiently individuals can handle cognitively demanding tasks.

Modern intelligence tests, such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS), assess multiple cognitive domains, including:

In the context of work, higher IQ scores are associated with faster learning, better adaptation to novel problems, and higher average performance in complex roles. However, IQ does not measure motivation, creativity, emotional intelligence, or job-specific expertise.

Average IQ scores vary across professions primarily because jobs differ in cognitive complexity. Roles that require abstract reasoning, long-term planning, and decision-making under uncertainty tend to attract—and retain—individuals with higher average cognitive ability.

Several mechanisms explain this pattern:

Importantly, these processes operate at the population level, not the individual level.

The following table summarizes commonly cited estimated average IQ ranges by occupational group, based on historical datasets, cognitive research, and workforce studies. These values should be understood as approximate averages, not entry requirements.

|

Profession Group |

Typical Cognitive Demands |

Estimated Average IQ |

|

Professors, Research Scientists |

Abstract reasoning, theory building |

135–145 |

|

Physicians, Lawyers, Engineers, Architects |

Complex problem-solving, formal logic |

125–135 |

|

Teachers, Accountants, Managers, Pharmacists |

Structured reasoning, planning |

115–125 |

|

Clerks, Police Officers, Sales Professionals, Electricians |

Applied reasoning, procedural decisions |

105–115 |

|

Skilled Trades, Machine Operators |

Technical execution, spatial skills |

95–105 |

|

Manual and Routine Labor |

Repetitive, concrete tasks |

85–95 |

Table 1. Estimated Average IQ by Occupational Group

Key point: IQ distributions overlap substantially across professions. Many individuals fall well above or below these averages within the same occupation.

A common mistake is to treat occupational IQ averages as thresholds. In reality:

For example, not all engineers have IQs above 130, and not all individuals in manual labor roles have low IQs. IQ by profession reflects probability trends, not deterministic outcomes.

Decades of research consistently show that IQ is the single strongest predictor of job performance across occupations, especially in cognitively complex roles. A landmark meta-analysis by Schmidt and Hunter (1998) found that general mental ability correlates strongly with job performance and training success across industries. The strength of this relationship increases as job complexity rises. However, IQ explains only part of performance variance. Motivation, conscientiousness, experience, and social skills also play substantial roles.

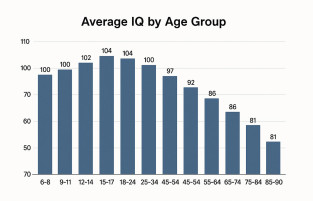

IQ score distributions across professions based on occupational data

Several misconceptions persist:

“IQ determines your career destiny.”

→ False. IQ influences probabilities, not outcomes.

“Low-IQ jobs require little intelligence.”

→ False. Many roles demand practical reasoning, skill, and experience not captured by IQ tests.

“You cannot succeed in a high-IQ profession without a high IQ.”

→ False. Individual variation is large, and compensatory strengths matter.

Understanding these limitations is essential to avoid misuse of IQ data.

While IQ influences how quickly someone learns and adapts, long-term career success depends on multiple factors:

|

Factor |

Role in Career Outcomes |

|

IQ |

Learning speed, problem-solving |

|

Experience |

Skill mastery, judgment |

|

Motivation |

Persistence, effort |

|

Personality |

Reliability, teamwork |

|

Opportunity |

Education, mentorship |

Table 2. Factors Affecting Career Determinants

High IQ may open doors, but sustained success depends on far more than cognitive ability alone.

IQ-by-profession data is valuable for:

However, ethical caution is essential. Using IQ as a rigid sorting mechanism risks reinforcing inequality and ignoring human potential beyond test scores.

Conclusion

IQ by profession reveals a statistical relationship between cognitive ability and job complexity, not a fixed rule about who belongs where. Higher average IQs appear in professions that demand abstract reasoning and long training, while lower averages appear in roles with more concrete or routine tasks.

Yet individual outcomes vary widely. IQ is best understood as one contributing factor among many, useful for describing patterns not defining people.

References