Abstract

IQ scores and educational attainment are consistently correlated, but the nature of this relationship has long been debated. Does higher intelligence lead individuals to pursue more education, or does education itself increase intelligence? Drawing on large-scale meta-analyses and longitudinal studies, this article examines how IQ varies by education level, why these differences appear, and what modern research reveals about the causal impact of schooling on cognitive ability.

“IQ by education level” refers to average IQ scores observed among groups with different levels of completed education, such as high school graduates, college graduates, or individuals with advanced degrees. At first glance, the pattern appears straightforward: People with more years of education tend to have higher average IQ scores. However, interpreting this relationship requires care. IQ is not merely a trait people bring into education, it is also shaped by educational experiences themselves.

Research using standardized tests such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) has repeatedly shown consistent group-level differences.

|

Education Level |

Approximate Average IQ |

|

General population |

100 |

|

High school graduates |

~105 |

|

College graduates |

~115 |

|

Master’s degree holders |

~120 |

|

PhD / MD holders |

~125 |

Source: Wechsler (1972); AssessmentPsychology.com; meta-analytic summaries

These values do not imply that everyone within a category shares the same intelligence. There is substantial overlap between groups. Still, the upward trend is robust across countries and cohorts.

There are two main explanations, often framed as selection vs. causation.

1. Selection: Smarter Students Stay Longer in School

Longitudinal studies show that early IQ predicts later educational attainment (Deary et al., 2007). This means part of the IQ – education link reflects who enters and remains in the education system.

2. Causation: Education Raises IQ

Crucially, modern research shows that education does more than select—it actively increases intelligence. A landmark meta-analysis by Ritchie & Tucker-Drob (2018) examined over 600,000 participants across 42 datasets using quasi-experimental methods. Their conclusion was clear: Each additional year of education raises IQ by approximately 1–5 points, depending on study design.

This effect:

Education is therefore not just correlated with intelligence, it is one of the most reliable ways to increase it.

Education does not raise all aspects of intelligence equally.

Fluid Intelligence

Education improves fluid abilities, especially during childhood and adolescence, though gains may taper later in life.

Crystallized Intelligence

These skills are especially sensitive to schooling and continue to grow with prolonged education. Studies using regression-discontinuity designs show that schooling effects are often stronger than age effects alone (Cahan & Cohen, 1989).

The Flynn Effect, the steady rise in average IQ scores across generations offers further evidence for education’s role. Improved schooling, longer education, and cognitively demanding environments are considered key drivers of this trend (Flynn, 1987).

Importantly:

No. While averages differ, individual variation is large. Many people without college degrees score well above average IQ. Many degree holders fall within the average range. IQ by education level reflects group tendencies, not destiny. Education raises the mean, not the ceiling.

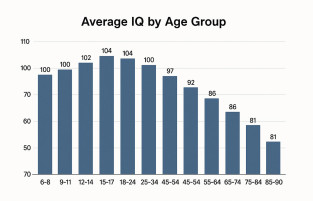

Average IQ varies across different education levels

The relationship between IQ and education level is neither accidental nor purely selective. Decades of research now show that education itself increases intelligence, often in lasting ways.

While higher IQ may open doors to education, education also builds the cognitive tools measured by IQ tests. In that sense, intelligence is best understood not as a fixed trait, but as a capacity that develops through sustained cognitive challenge – and education remains one of its most powerful engines.

References: