Abstract

IQ (intelligence quotient) is often discussed as if it were an inborn, fixed trait. Contemporary research, however, shows that intelligence is a complex characteristic shaped jointly by genetic and environmental influences. Thousands of genetic variants contribute small effects, while environmental factors within the normal range such as education, health, and living conditions can exert substantial influence. This article synthesizes evidence from twin and adoption studies (heritability research) and molecular genetics (genome-wide association studies, GWAS), and clarifies a common misconception: high heritability within a group does not justify attributing differences between groups to genetic causes.

The Scientific Answer: It’s More Complicated Than That

Across medical and genetic science sources, a consistent framework emerges: intelligence is a multifactorial trait, influenced by both genetics and environment. Education, nutrition, healthcare, family context, and learning opportunities all shape cognitive development.

Importantly, genetic research has not identified a single “IQ gene.” Instead, intelligence reflects the combined influence of many genes, each contributing only a very small effect.

Key points:

Genes and brains illustrating intelligence variation

In behavioral genetics, heritability (often written as h²) refers to the proportion of variation in a trait within a specific population and environment that is statistically associated with genetic differences between individuals.

Heritability does not mean:

These are all conceptual errors.

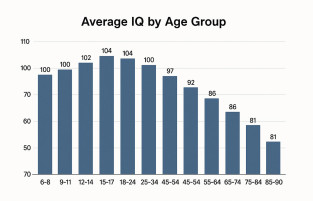

Meta-analyses show that heritability of cognitive ability tends to increase from childhood into adulthood. This pattern likely reflects two processes: genetic influences becoming more expressed over time, and environmental variation becoming more uniform in some life stages. Heritability is therefore context-dependent, not a biological constant.

Genome-wide association studies examine large populations to identify genetic variants statistically linked to intelligence. Across studies, the findings are consistent:

Large-scale GWAS have identified numerous loci associated with intelligence, reinforcing the polygenic model.

Recent reviews emphasize that while genetic variation correlates with differences in intelligence and some brain-related markers, the biological mechanisms remain incompletely understood. Moving from genetic correlation to causal explanation requires caution.

Even when heritability within a group is relatively high, environmental factors can still produce large differences in IQ scores and cognitive skills. Modern intelligence genetics consistently highlights the influence of: education quality and duration, childhood nutrition and health, family conditions and cognitive stimulation, chronic stress and deprivation.

In short, genetic influence and environmental influence are not competing explanations; they operate together.

A common mistake in public debates (notably in controversies surrounding The Bell Curve) is the following reasoning:

“If IQ is highly heritable within Group A, and Group A differs from Group B in average IQ, then the difference between A and B must be genetic.”

This inference is flawed because it confuses two meanings of “genetic”:

Heritability is a population- and context-specific statistic, not a universal explanation of group differences. Philosophical and scientific analyses of heritability have repeatedly emphasized that within-group heritability cannot explain between-group differences.

Guidelines for responsible discussion of IQ and genetics:

Understanding these distinctions allows for more accurate science communication and helps prevent the misuse of genetics in social and political arguments.

Reference: