Over the last century, IQ test has gone from a classroom screening tool in Paris to a family of standardized assessments used in schools, clinics, and research labs. This guide gives an overview of how IQ testing began with Alfred Binet, how it evolved through major American revisions, why the Wechsler scales changed the scoring model, and what modern psychometrics and ethics mean for using these tests today.

In the late 1800s, psychologists experimented with timing reactions, sensory thresholds, and other basic tasks to capture “mental ability.” These efforts advanced measurement and statistics, but they didn’t directly assess higher-order thinking such as reasoning, working memory, and problem-solving, the skills most relevant to learning and day-to-day cognition (Spearman, 1904).

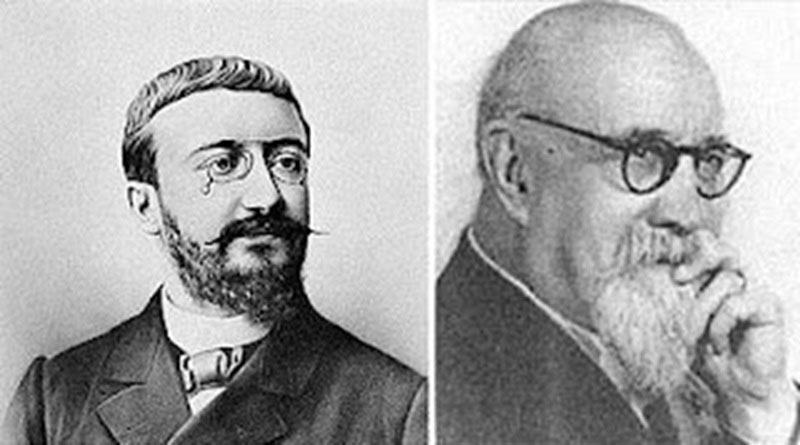

In 1904, the French Ministry of Education asked Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon to identify children who needed extra academic support. They built a scale of tasks that targeted attention, memory, and problem-solving abilities not tied to specific classroom content. The result, the Binet–Simon Scale (1905), is widely regarded as the starting point of modern intelligence testing (Binet & Simon, 1905/1916). Binet introduced the idea of mental age and emphasized that test scores are practical estimates not permanent labels and that intelligence can change with experience.

Binet & Simon - Father of the first IQ test

In the United States, Lewis Terman adapted and standardized Binet’s work, publishing the Stanford–Binet in 1916 and popularizing the ratio formula IQ = (Mental Age ÷ Chronological Age) × 100 (Terman, 1916). With large-scale norms, scores became comparable across examinees of the same age, and the test quickly became a leading tool for educational decisions and developmental research.

During World War I, the U.S. Army had to classify huge numbers of recruits. Psychologists developed two large-scale tests: Army Alpha (written, verbal) and Army Beta (nonverbal pictorial tasks for low-literacy or non-English speakers). The program proved standardized testing could be deployed at scale, but also foreshadowed misuses and simplistic interpretations of results in policy contexts (Yerkes, 1921).

David Wechsler addressed the ratio method’s limitation for adults by introducing the Deviation IQ, locating an individual’s performance relative to age-peer norms (mean 100, SD 15). His family of tests—WAIS (adults), WISC (children), WPPSI (preschool)—shifted attention from a single number to a profile of index scores (e.g., Verbal Comprehension, Perceptual/Fluid Reasoning, Working Memory, Processing Speed) plus a Full-Scale IQ summary (Wechsler, 2008).

Beneath test design, theories of intelligence evolved from Spearman’s g (a general factor explaining positive correlations among diverse tasks) to Thurstone’s Primary Mental Abilities, then the Cattell–Horn split between fluid (Gf) and crystallized (Gc) abilities, and finally Carroll’s comprehensive Three-Stratum model (Spearman, 1904; Thurstone, 1938; Cattell, 1963; Carroll, 1993). These strands merged into the widely used CHC framework, which guides modern batteries and ensures subtests map to well-specified cognitive abilities (McGrew, 2005).

The second half of the 20th century transformed how IQ tests are built and scored:

An IQ score is a standardized estimate with a standard error of measurement and confidence intervals. Scores are influenced by test conditions, health, effort, and familiarity with testing. IQ tests estimate general reasoning and related abilities; they do not directly measure creativity, values, motivation, character, or life potential. Used properly and alongside other information they remain among psychology’s most validated tools for certain academic and training outcomes (AERA et al., 2014; Schmidt & Hunter, 1998).

The history of IQ testing includes clear misuses, from eugenic arguments to sweeping claims about groups. Modern practice responds with clear purposes, standardized procedures and accommodations, fairness analyses such as differential item functioning (DIF), and responsible interpretation that reports uncertainty and considers educational/medical history (AERA et al., 2014; Zumbo, 1999).

Despite debate, IQ assessments play defined roles across contexts:

From Binet’s classroom tool to today’s adaptive batteries, the history of IQ testing is a story of practical goals, theoretical refinement, statistical innovation, and ethical course correction. When developed and used under modern standards, IQ tests provide a reliable window into core cognitive abilities, one piece of a larger picture that also includes personality, motivation, health, and opportunity (AERA et al., 2014; Carroll, 1993).

References